Scroll down to read the English version

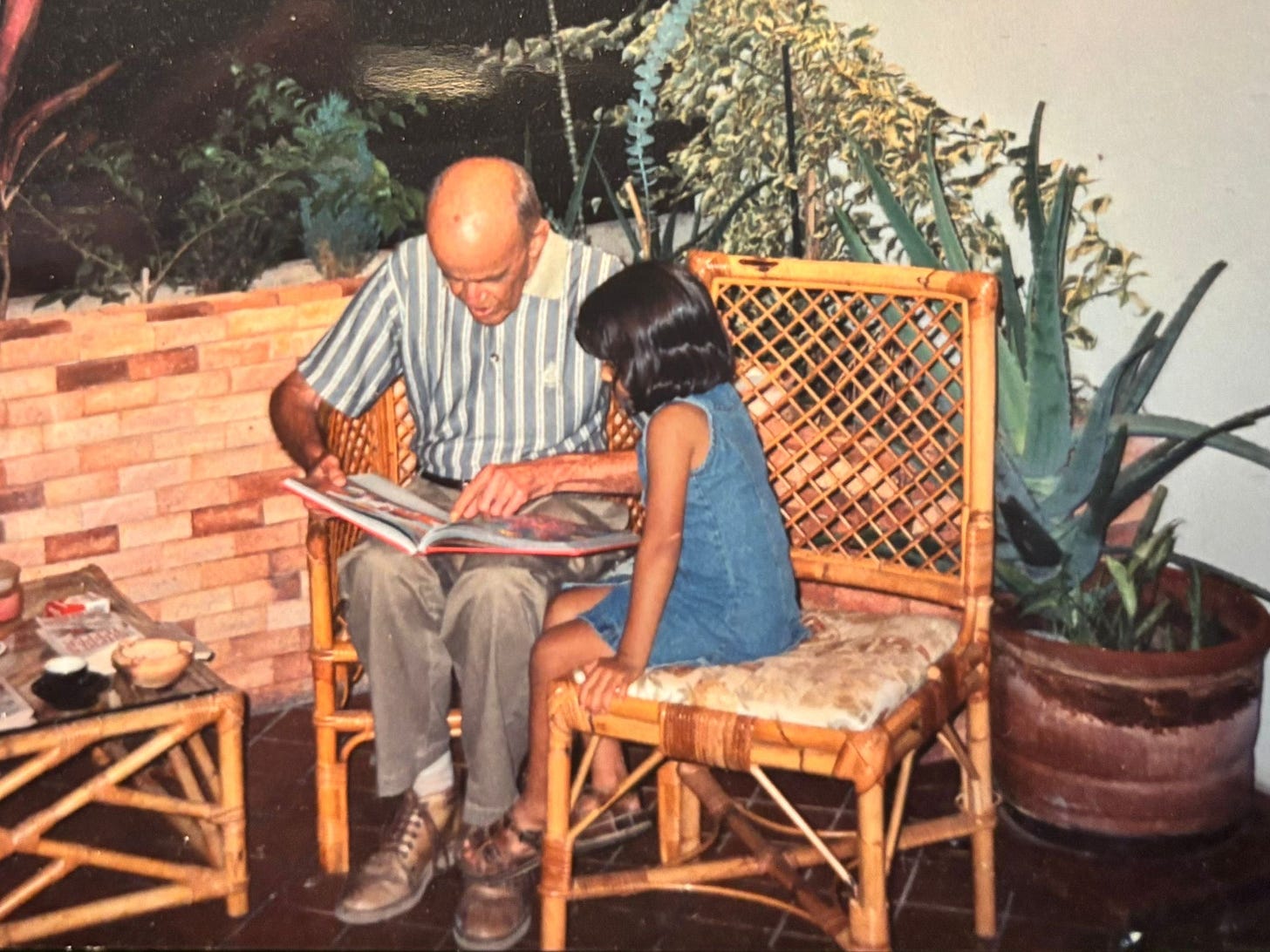

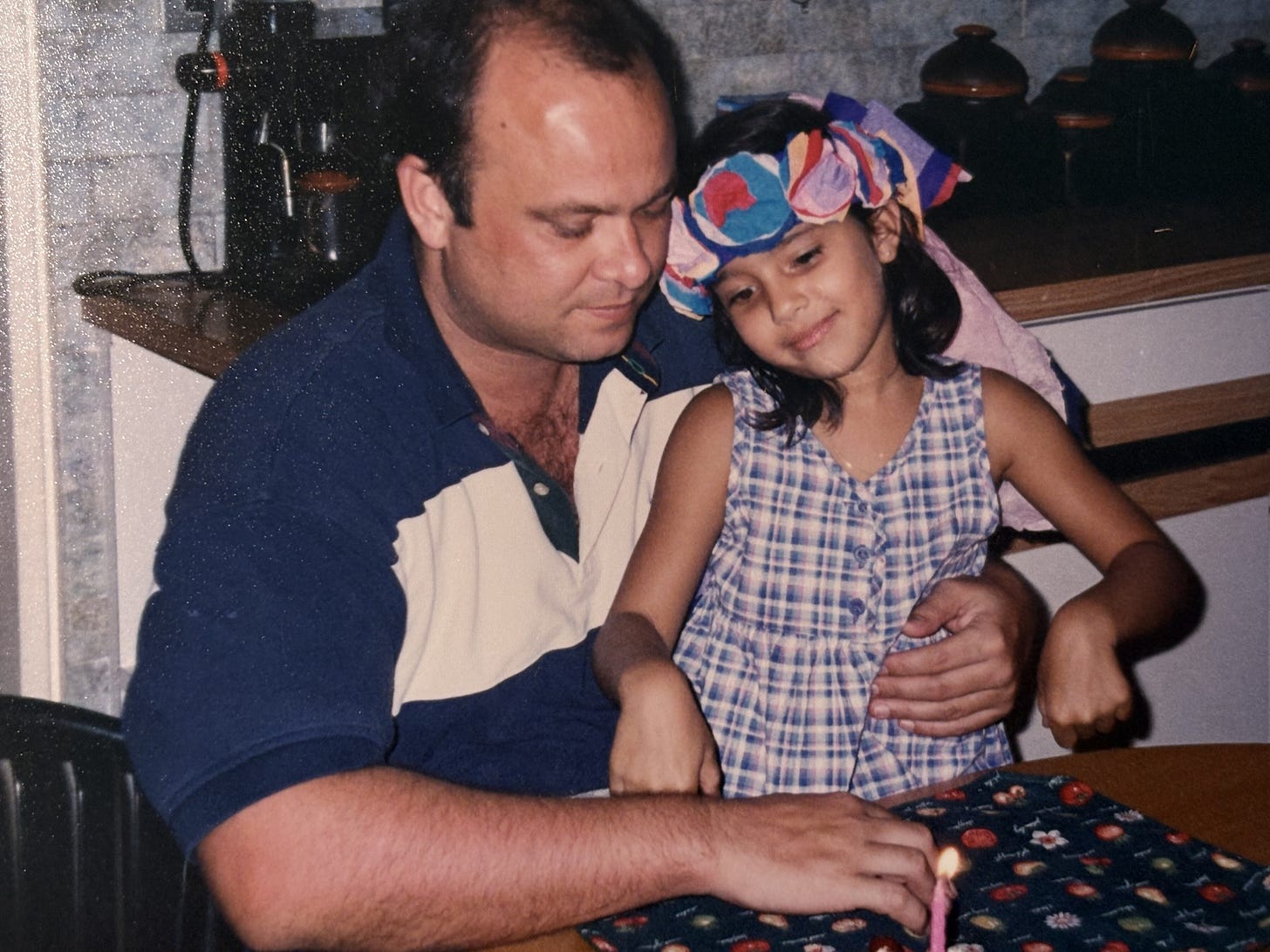

Tenía ocho años cuando mi padre me sentó en la cocina para decirme que nos íbamos inmediatamente del país. No usó las palabras “huida”, “secuestro”, “asesinato”, “exilio”, “pobreza” o “dictadura” para justificar la urgencia. En su lugar, me ofreció una escena que él y su mujer habían vivido hacía pocos días: francotiradores del gobierno chavista disparando a manifestantes en la marcha a la que no me habían permitido ir. Yo no sabía lo que eran los francotiradores, pero sí entendí que había muerto gente y que podría haber sido yo misma si hubiese acudido. Aun así, mi padre se acordó de que era una niña y usó una palabra con la que me encandiló: “perrito”. Me dijo, justo después de informarme de que no vería a mi madre en uno o dos años: “Por fin vas a tener un perrito.”

La historia del perro empieza dos años atrás, cuando, con seis, le suplico que me regale una mascota. Y termina con el dato de que mi primer perro fue una perrita que adopté a los veinticuatro años, en Barcelona, ciudad a la que nos iríamos poco después de esa conversación en la cocina.

Le malvendimos el apartamento a un matrimonio chavista. Al año siguiente, regresé a Caracas para ver a mi madre. Le pedí que me llevara hasta el que había sido mi edificio. Me subí al ascensor y toqué el timbre. Me abrió la mujer. No sé si no me reconoció porque había ganado un poco de peso o porque nunca se llegó a fijar en mí. Le expliqué que yo había vivido ahí. Fue muy amable y me dejó pasar. El apartamento estaba lleno de esculturas de mármol, jarrones de un material que parecía oro, tapices de pieles exóticas y retratos hiperrealistas de la pareja. Mi cuarto lo habían convertido en la oficina de su marido, que trabajaba para el gobierno de Chávez. La señora me ofreció una galleta. La acepté. No lo necesitaba, pero ella me guió hasta la cocina. El recorrido de mi cuarto hasta la cocina era corto y lo había hecho miles de veces. La galleta era de una marca que no conocía. “Son riquísimas; nos las traen de Inglaterra.” Le di un mordisco y sonreí. No le dije que hubiese preferido un pirulín.

Donde año y medio atrás había estado colgado un reloj de pared, se encontraba una fotografía de Hugo Chávez enmarcada e iluminada.

Salí del apartamento sintiéndome insatisfecha, pero sin entender por qué. Me pasé el resto de las vacaciones encerrada por el pánico que me generaba salir a la calle, viendo Gilmore Girls en casa de mi mejor amiga y comiendo mis chucherías venezolanas favoritas.

Un año y medio más tarde, mi madre consiguió salir del país para instalarse en Barcelona. El billete se lo regaló un amigo porque ella no lo podía pagar, como tampoco se podía pagar vivir en Barcelona. Cambió su sueño de ser actriz por cuidar a ancianos y a gente con discapacidades. El esfuerzo valía la pena. A los cuatro años de su mudanza, Chávez cerró RCTV, el canal de televisión que le había dado doblajes de novelas y cuñas publicitarias. También era un canal que se mostraba crítico con el gobierno. Era 2007. Ya llevábamos 8 años de régimen.

Dos años después del cierre de RCTV, mi padre me enseñó un vídeo en YouTube en el que sale Hugo Chávez diciendo una de sus frases célebres: “Nosotros no queremos ser ricos; ser rico es malo.” Yo me acordé de la galleta inglesa y el derroche de opulencia con el que habían llenado el apartamento de ciento treinta metros cuadrados que le habíamos vendido a los que no querían ser ricos. Lloré de frustración y le pregunté a mi papá cómo podía ser posible. Él me explicó tres cosas sobre la naturaleza humana. Me pidió que no llorara. Yo le dije que me daba asco que esa gente viviera en el que había sido nuestro hogar. Me dijo que no me preocupara, que hacía años que no vivían ahí. Se habían mudado a una mansión. Ese apartamento lo tenían vacío, como muchos otros que se habían comprado después.

Después o antes de ver ese vídeo, no me acuerdo, hubo un momento en que le pedí a mi madre que no me explicara ninguna noticia de Venezuela porque estaba harta de escuchar el horror. Pero no estaba harta de escuchar el horror; se me hacía insoportablemente doloroso. Con quince años, no tenía herramientas para gestionar la rabia y el sentimiento de injusticia. A día de hoy sigo sin saber hacerlo.

Durante esa época de supuesta tregua noticiera me llegaron algunas escenas que intensificaron el sentimiento de culpabilidad por estar a salvo. Secuestran al padre de mi mejor amiga y vecina. Tiene suerte: no lo matan. La pensión mensual de mi abuela le alcanza para pagar un desayuno muy mediocre donde yo vivo. Hay apagones de luz constantemente en todo el país. Muere Chávez. No hay harina PAN en los supermercados. Sube Maduro. Los hospitales no tienen material quirúrgico. Tampoco tienen medicamentos. La gente pasa hambre. La inflación deja pasar el bolívar a la historia. Todo se paga en dólares. Los colectivos motorizados tienen impunidad para hacer lo que quieran, incluso asesinar civiles que hablan en contra de la dictadura. Mejor dicho, el régimen incentiva a los colectivos para que terroricen a la población. Hay tanta pobreza que te pegan un tiro para robarte. Miles de presos políticos son torturados en el Helicoide, casualmente el centro de torturas más grande de Latinoamérica, y otras cárceles. Uno es el padre de un niño que fue conmigo al colegio. Colas de horas para poner gasolina. Mi abuela se levanta a las cinco de la mañana para conseguir gasolina. Hay días en que no la consigue. No hay papel tualé. Matan a una niña que conocía. Torturan y asesinan a universitarios. Ejecutan a disidentes. Mi abuela lo pierde todo, pero por fin consigue salir del país. Mis tías hace años que lo lograron. Más de un ochenta por ciento de la población está sumida en la pobreza absoluta.

No conozco a nadie que siga en Venezuela. Venezuela está siendo borrada. Venezuela: el país con la reserva de petróleo más grande del mundo. Petróleo que financia cuentas multibillonarias en Suiza, relojes carísimos que ni intentan esconder en la televisión pública y galletas inglesas para los que gritan que ser rico es malo. Pero no es solo del petróleo de donde sacan el dinero.

Pasan y han pasado muchas más cosas espantosas que se pueden buscar en internet. O que te las puede contar cualquier venezolano o venezolana que conozcas. Hay millones de historias espeluznantes y dolorosas esperando a ser escuchadas. Cuando digo millones, no es una figura literaria. Son millones de verdad.

Se acercan las elecciones de julio de 2024. Estamos pasando una semana con mi familia materna. En la mesa se habla de las elecciones. Yo me cierro en banda. Sé que se las van a volver a robar; al fin y al cabo, el gobierno controla el CNE. Mi abuela, cuya personalidad se parece bastante a la mía, está de acuerdo y no quiere ni hablar del tema. Prefiere narrarnos que quiere encontrar pareja y que miente respecto a su edad para conseguirlo. Se quita cinco, siete y hasta diez años. Le cuesta mantener un registro mental de a quién le dice qué edad y se arrepiente de no haber llegado a una misma cifra para todo el mundo. Yo también prefiero escuchar las desventuras amorosas de mi abuela antes que pensar en que posiblemente no vaya a morir en el lugar que más ama del planeta.

Las elecciones se ganan con más de un 70 por ciento de los votos. Se las roban. Las actas que confirman la victoria aplastante de la oposición son presentadas, observadas y analizadas en lugares internacionales importantes con señores encorbatados y mujeres con stilettos. Todos miran a otro lado porque no hacerlo implicaría algo que no interesa: intervenir.

Es el tres de enero de 2026 y mi marido me despierta a las 5:13 de la madrugada con las siguientes palabras: “Trump ha bombardeado Caracas y capturado a Maduro.” Medio dormida, recibo las noticias que llevo esperando desde que tengo ocho años: la posibilidad de que le llegue el fin al chavismo que lleva enquistado en mi país desde 1999. Veintiséis (el dos de febrero serán veintisiete) años de dictadura se dice rápido. Aunque yo suelo tardar en hacer el cálculo porque no se me dan muy bien las matemáticas. Pero estos días lo digo rápido porque todo el mundo lo dice. Porque estos días todo el mundo habla de Venezuela.

Hay una cosa que es punzante de una manera casi perversa: los partidos o pensadores políticos con los que simpatizo nos dan la espalda a los venezolanos. Se muestran tibios a la hora de condenar los crímenes de lesa humanidad del régimen. Y los partidos cuyas políticas y discursos me horrorizan son los que sí reconocen el horror que llevamos viviendo durante casi tres décadas. Regreso a esas tres cosas que me dijo mi padre sobre la naturaleza humana con su español mal conjugado y articulado: “El naturaleza humano es simple, corrupto y como decía tu Opa: casi todos somos putas, lo único que cambie es el precio.” Aun así, después del chiste, es inaguantable que tu país se haya convertido en la herramienta escuálida que ayuda a avanzar agendas políticas por un lado y por el otro. El país que dejó de ser país porque un tercio de sus habitantes huyó y ahora es solo un símbolo. Un símbolo que, además, tiene la fuerza para ahogar, silenciar y reprimir a los que no han podido escapar.

Una persona de internet me dice algo muy interesante: que me calle, que yo no puedo hablar porque a día de hoy soy una privilegiada. Su ira me genera una pregunta: ¿Un relato es más válido si su narrador no prospera? O dos: ¿Tiene el narrador que quedarse en la mierda para que lo escuchen? O tres: ¿Es esa la fantasía erótica de la gente privilegiada de verdad (the ultimate white wet dream): que los que han temido por su vida y/o han conocido la miseria no salgan nunca de ella?

La persona que me grita que me calle parece una persona blanca normal. Las pocas fotos que ha colgado en su perfil me indican que le gusta dar paseos por la orilla del mar, que disfruta del yoga, que lee en cafeterías de especialidad y que nunca ha huido de un país sin saber si podría volver a ver a su madre. Cuando busco su mensaje para releerlo, me doy cuenta de que lo ha borrado.

No sabemos qué va a pasar y lo que más miedo nos da es que esto solo sea un capítulo más en la interminable historia del régimen. El petróleo lleva décadas sin ser de los venezolanos.

Escribiendo esto, así como viviendo cada día de mi vida, me invade el miedo de no ser venezolana o de ser una venezolana impostora porque perdí el acento al año de llegar a Barcelona. No me sabría ubicar en Caracas. Creo que sí podría llegar hasta la Cotamil, Parque del Este o El Ávila. Me sé el himno, pero hay tramos de la letra que se me escurren. Mi historia no tiene un final trágico, más allá de la fractura familiar, moral y psicológica. Lamentablemente, la de la identidad quebrada y desplazada es una auténtica historia venezolana contemporánea.

Al menos tengo mi pinta, que es de 100% Veneka.

P.D. Publico este texto en los dos idiomas porque fue escrito así: algunos párrafos en inglés, otros en español. A veces incluso mezclando los dos idiomas en la misma frase.

ENGLISH VERSION:

I was eight years old when my father sat me down in the kitchen to tell me that we were leaving the country immediately. He didn’t use words “escape,” “kidnapping,” “murder,” “exile,” “poverty,” or “dictatorship” to justify the urgency. Instead, he offered me a scene he and his wife had witnessed a few days earlier: snipers from the Chavista government firing at protesters during a march I hadn’t been allowed to attend. I didn’t know what snipers were, but I did understand that people had died and that it could have been me if I’d gone. Still, my father remembered that I was a child and used a word that bewitched me: “puppy.” Right after telling me that I wouldn’t see my mother for one or two years, he said, “You’re finally getting a puppy.”

The puppy story begins two years earlier, when I was six and begged him to get me a pet. And it ends with the fact that my first dog was the one I adopted at twenty-four, in Barcelona—the city we would move to shortly after that conversation in the kitchen.

We sold the apartment for a quarter of its price to a Chavista couple. The following year, I went back to Caracas to see my mother. I asked her to take me to what had once been my building. I took the elevator up and rang the doorbell. The woman opened the door. I don’t know if she didn’t recognize me because I’d gained a bit of weight or because she’d never really noticed me to begin with. I explained that I had lived there. She was very kind and let me in. The apartment was full of marble sculptures, vases made of something that looked like gold, tapestries of exotic skins, and hyper-realistic portraits of the couple. My bedroom had been turned into her husband’s office; he worked for Chávez’s government. The woman offered me a cookie. I accepted it. I didn’t need it, but she guided me to the kitchen. The walk from my bedroom to the kitchen was short, and I’d done it thousands of times. The cookie was from a brand I didn’t recognize. “They’re delicious; we get them imported from England.” I took a bite and smiled. I didn’t tell her I would’ve preferred pirulín.

Right where a wall clock had hung a year and a half earlier, there was now a framed, illuminated photograph of Hugo Chávez.

I left the apartment feeling dissatisfied, without understanding why. I spent the rest of the vacation locked indoors, panicked at the thought of going outside, watching Gilmore Girls at my best friend’s house, and eating my favorite Venezuelan snacks.

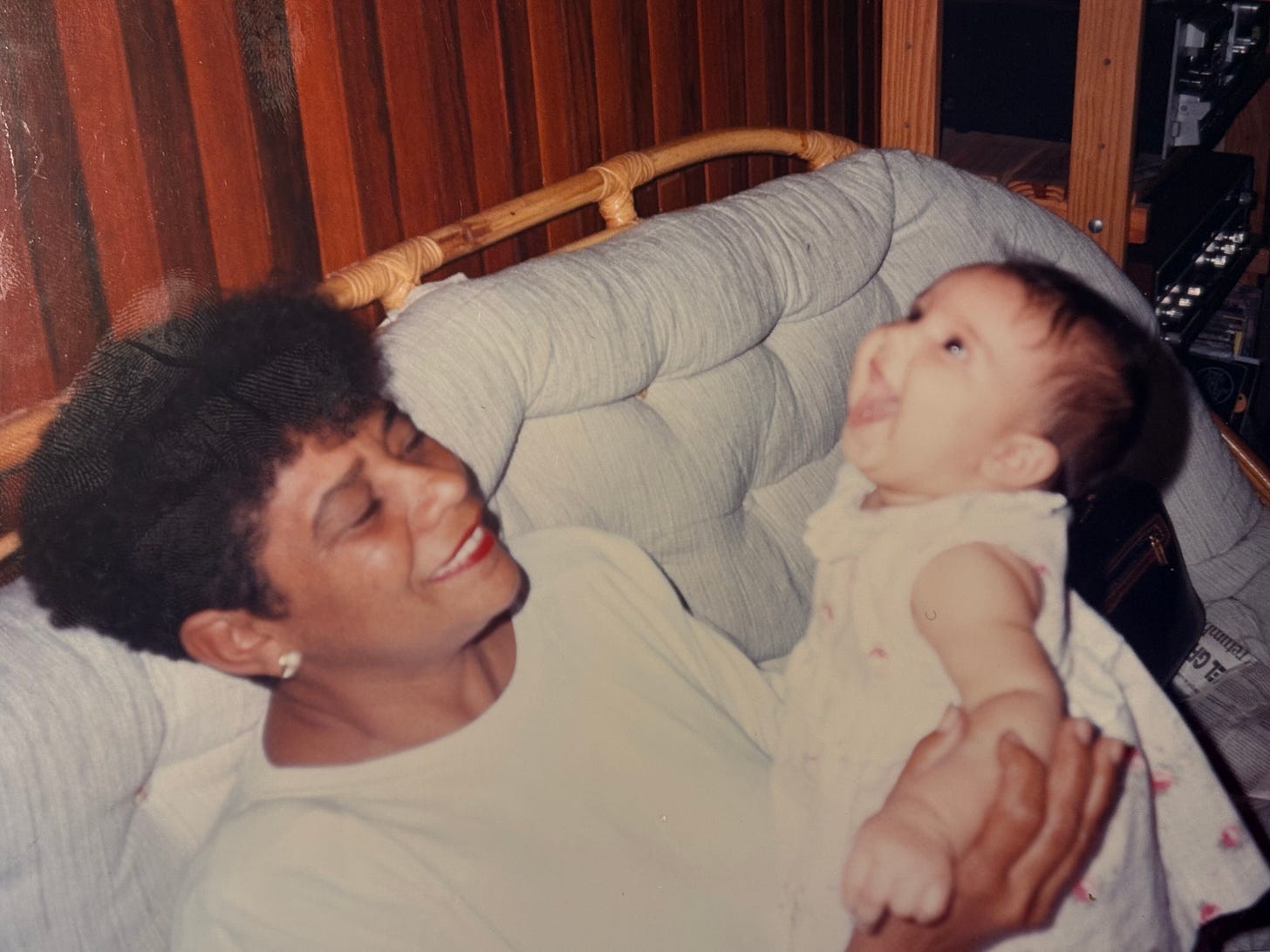

A year and a half later, my mother managed to leave the country and settle in Barcelona. A friend gave her the money for the plane ticket because she couldn’t afford it, just like she couldn’t afford to live in Barcelona. She traded her dream of being an actress for caring for the elderly and people with disabilities. The effort was worth it. Four years after her move, Chávez shut down RCTV, the TV channel that had given her soap-opera dubbing jobs and commercial gigs. It was also a channel that criticized the government. It was 2007. We had already been under the regime for eight years.

Two years after RCTV was shut down, my father showed me a YouTube video of Hugo Chávez saying one of his famous quotes: “We don’t want to be rich; being rich is bad.” I remembered the English cookie and the lavish display of opulence that had filled the 1,350-square-foot apartment we had sold to the people who didn’t want to be rich. I cried in frustration and asked my dad how that could be possible. He explained three things to me about human nature. He asked me not to cry. I told him it disgusted me that those people lived in what had been our home. He told me not to worry, that they hadn’t lived there for years. They’d moved into a mansion. They kept that apartment empty, like many others they’d bought afterward.

Before or after seeing that video, I don’t remember the timeline, there was a moment when I asked my mother not to explain any news from Venezuela to me because I was sick of hearing the horror. But I wasn’t sick of it; it was just unbearably painful. At fifteen, I had no tools to manage the rage and the sense of injustice. To this day, I still don’t know how to do it.

During that supposed news truce, some scenes reached me anyway, intensifying the guilt I carried for being safe. My best friend’s (and neighbor) father is kidnapped. He’s lucky: he doesn’t get killed. My grandmother’s monthly pension would only allow her to buy a mediocre breakfast where I live. There are constant power outages across the country. Chávez dies. There’s no Harina PAN in supermarkets. Maduro rises to power. Hospitals have no surgical supplies. They don’t have medicine either. People are starving. Inflation buries the bolívar into the past. Everything is paid for in dollars. Armed “Colectivos” (gangs) have impunity to do whatever they want, including murdering civilians who speak out against the dictatorship. Or rather, the regime encourages the colectivos to terrorize the population. There’s so much poverty that people shoot you to steal your phone. Thousands of political prisoners are tortured at El Helicoide, which is coincidentally the largest torture center in Latin America, and in other prisons. One of them is the father of a kid I went to school with. Hours-long lines to get gas. My grandmother gets up at five AM to try to get gas. Some days she doesn’t find any. There’s no toilet paper. A girl I knew is murdered. College students are tortured and killed. Dissidents are executed. My grandmother loses everything, but finally manages to leave the country. My aunts left years ago. Over eighty percent of the population is living in absolute poverty.

I don’t know anyone who’s still in Venezuela. Venezuela is being erased. Venezuela: the country with the largest oil reserves in the world. Oil that funds multibillion-dollar Swiss accounts, outrageously expensive watches they don’t even try to hide on public television, and English cookies for those who shout that being rich is bad. But oil isn’t the only place the money comes from.

Many more horrifying things have happened, and are still happening, that you can look up online. Or that any Venezuelan you know can tell you about. There are millions of gruesome, painful stories waiting to be heard. When I say millions I mean millions, literally.

It’s 2024 and the July elections are coming up. We’re spending a week with my mother’s family. At the table, we talk about them. I shut down completely. I know they’re going to steal them again; the government controls the electoral council after all. My grandmother, whose personality is a lot like mine, agrees and doesn’t want to talk about it. She’d rather tell us that she wants to find a partner and that she lies about her age to do so. She shaves off five, seven, even ten years. She has trouble keeping track of who she’s told which age to and regrets not settling on one number for everyone. I also prefer listening to my grandmother’s romantic misadventures than thinking about the possibility that she won’t die in the place she loves most on earth.

The elections are won with more than seventy percent of the vote. They steal them. The documents proving the opposition’s landslide victory are presented, observed, and analyzed in important international rooms by men in suits and women in stilettos. Everyone looks the other way because not doing so would imply something inconvenient for them: intervention.

It’s January 3, 2026, and my husband wakes me at 5:13 a.m. with the following words: “Trump bombed Caracas and captured Maduro.” Half asleep, I receive the news I’ve been waiting for since I was eight years old: the possibility that the end has come for the Chavismo that has been embedded in my country since 1999. Twenty-six years of dictatorship (twenty-seven on February second) is easy to say. Even though I usually take a while to do the math because I’m bad with numbers. But these days I say it quickly because everyone does. Because these days everyone is talking about Venezuela.

Something stings in a perverse way: the political parties or thinkers I sympathize with turn their backs on Venezuelans. They’re lukewarm when it comes to condemning the regime’s crimes against humanity. And the parties whose policies and rhetoric horrify me are the ones who do acknowledge the horror we’ve been living through for nearly three decades. I go back to those three things my father told me about human nature, in his poorly conjugated, clumsy Spanish: “Human nature is simple, corrupt, and like your Opa used to say: almost everyone’s a whore—the only thing that changes is the price.” Even so, after the joke, it’s unbearable that your country has become a flimsy tool used to push political agendas from one side and the other. The country that stopped being a country because a third of its people fled and is now just a symbol. A symbol that still has the power to suffocate, silence, and repress those who can’t escape.

Someone on the internet tells me something very interesting: to shut up because today I’m privileged. Their anger sparks a question: Is a story more valid if its narrator doesn’t succeed? Or two: Does the narrator have to stay in misery to be heard? Or three: Is that the erotic fantasy of the truly privileged (the ultimate white wet dream) that those who’ve feared for their lives and/or known misery never escape it?

The person yelling at me to shut up seems like a normal white person. The few photos on their profile suggest they like beach walks, enjoy yoga, read in coffee shops, and have never fled a country without knowing whether they’d see their mother again. When I go back to reread their message, I realize they’ve deleted it.

We don’t know what’s going to happen, and what scares us most is that this may just be another chapter in the endless story of the regime. The oil hasn’t belonged to Venezuelans for decades.

As I write this, and as I go about every day in my life, I’m invaded by the fear of not being Venezuelan, or of being a Venezuelan impostor, because I lost my accent a year after arriving in Barcelona. I wouldn’t know how to get around Caracas. I think I could make it to la Cotamil, Parque del Este, or El Ávila. I know the national anthem, but parts of the lyrics slip away. My story doesn’t have a tragic ending, beyond my family’s economic, moral, and psychological fracture. Unfortunately, the story of a broken, displaced identity is an authentic contemporary Venezuelan tale.

At least I still have my look, which is 100% Veneka.

First substack to ever make me cry , but the chills came first. so beautifully written. Everyone should read this

I can't stop thinking about this, especially when you got called privileged. I don't know much about this but I don't think sacrifice and privilege are friends, and you sacrificed your home and family. I know safety is granted to everyone in this world, but I don't think it should go under the banner of privileged either. all my love xx